After providing year-end recommendations for 2008 and 2009, I thought I'd try something different this time. I asked some Signal poets (present and future) for books they enjoyed in the last twelve months. Here's what I got back.

Mark Callanan

Mark CallananI don’t know if I’d call it the “best” book of the year, and it wasn’t actually published in 2010 (so I’m delinquent on two accounts), but Luke Kennard’s The Harbour Beyond the Movie (Salt) is something that caught my attention earlier this year. I’d read his poem “The Murderer” in a Forward anthology a couple of years back and was blown away by it (Mob-style execution, multiple Tommy guns—think Sonny Corleone’s toll bridge death scene). It was one of those poems that confounds and delights, that makes one think: Oh, you can do that with poetry? Who knew? The whole collection, in fact, is exhilarating and disorienting, proceeding as it does by surreal narratives, like fun-house mirrors that make the familiar foreign, and in so doing, underline the modern world's many absurdities.

Mary Dalton

This year has been such that I've fallen a bit behind in reading the books of the year--am catching up on some of last year's, indeed. One that I thought highly of from 2009 is John Glenday's Grain (Picador) Daryl Hine's serial poem & (Fitzhenry & Whiteside) comes to mind among this year's books. Susan Glickman

Susan GlickmanSteven Heighton's Patient Frame (Anansi) is a formally elegant and morally resonant book, ranging in topics from the political to the domestic. The collection includes tributes to those who resisted evil, such as Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson, who stopped the My Lai massacre "as if to save was also labour/ for male arms", as well as to

The small-scale makers of precious obscurios—pomegranate spoons, conductors' batons, harpsichord tuning hammers, War of 1812 re-enactors' ramrods, hand-cranks for hurdy-gurdies.

It excoriates a child-molesting choir-master

who–while earth slowly unstrings a boyin his lento measure of staved ground—still savours the tangof August tomatoes, chords of Fauré’s Requiem(two years served, in fairway minimum)and the rectifying esteem of upstanding Ang-lican pals.

as well as pondering how and when one stops reading bedtime stories to one’s child:

How does the end enter? There's a hinginglike a book's sewn spine in the raw matterof time—that coded text, illegible—and stretched too far, it goes.

As these examples suggest, the book is full of those frissons of recognition that make reading poetry a way of reintroducing one to one's own soul.

Richard Greene

I'll plunk for Derek Walcott's White Egrets (FSG). Long line, large rhetoric, he takes the kind of risks that terrify Canadian poets. The form honours the largeness of an impassioned life. He grieves, he regrets, he returns from exile, he prepares to die, and he turns it all to music.

Jason Guriel

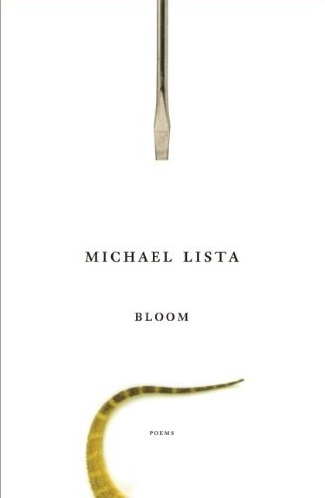

Bloom (Anansi) by Michael Lista is a first book of poetry that will give its creator no cause to wince in the years to come, and ought to put the rest of the literary world on notice. It isn’t juvenilia or, worse, promising. Instead, like Joyce’s Ulysses and Lennon and McCartney’s “A Day in the Life,” Lista’s assured book speaks fluently in various tongues as it takes the measure of an apocalyptic final day in one's scientist's quiet life.

Jason Guriel

I’ve been reading Christian Wiman’s third collection, Every Riven Thing (FSG), for a few years now, which is to say I’ve made sure to keep up with the magazines smart enough to publish its excerpts. Wiman writes instant classics that speak for themselves, speak about grief and God, and all but demand to be quoted: poems in which a tree “seems cast / in the form of a blast / that would have killed it,” and “leaves shush themselves like an audience,” and “wind seeks and sings every wound in the wood.”