Breaking news. Literary exhortation. Entertainments. And occasionally the arcane.

Wednesday, 30 March 2016

Tuesday, 29 March 2016

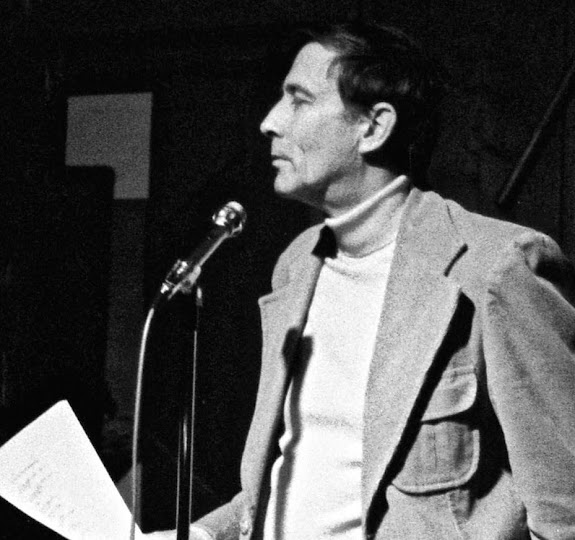

Flash Interview #12—Vincent Colistro

Vincent Colistro poems have appeared in The Walrus, Hazlitt, Geist and Arc. He was a prize-winner in the 2012 Short Grain contest, and was nominated for National Magazine Award for Poetry in 2014. He lives in Toronto. Late Victorians, his first book of poetry, was published this month by Vehicule Press.

Carmine Starnino: What is a "Late Victorian"?

Vincent Colistro: In Victoria, where I’m from, you can still see the Victorian era’s colonial thumb (skeletal as it is) wiped over everything. There are teahouses that sell expensive doilies and china, sweet shops that continue to import spotted dick and canned treacle, pubs that will pull you a warm bitter as you sit under a portrait of one of the queens. Oh, and gardens. Many many gardens. Then there’s the Empress Hotel, this Edwardian testament to opulence standing over the Inner Harbour. There’s actually a room in there called the Bengal Lounge, which is pretty much a fetish shop for colonialists. It has a tiger’s skin mounted on the wall and steam trays of mild curry to eat with your cocktails.

Anyways, I think I got a little off track. A Late Victorian is equal measures reputable and degenerate. I’m drawn to the idea of crumbling opulence, and, to me, that’s what a Late Victorian is.

It’s also, literally, a dead person from Victoria. So there’s that too.

CS: The middle of the book is given over to the eponymous verse play. What do you like about the form?

VC: I’ve always been more comfortable in mimicry. The book has a lot of first-person poems and most of them are not meant to be your author speaking. Even some of the poems in the third person rely so heavily on free indirect speech they might as well be a monologue. Earlier versions of the play were written like a normal poem, but I thought, why not push this chatter, this plurality of voices into its rightful form? For Plato, that kind of poetry was problematic ethically—it flew in the face of the unified life, its multiplicity somehow nefarious. So… I guess the verse poem is also my way of sticking it to Plato.

CS: The poems are filled with grim, often apocalyptic hints: funerals, massive meteors, city-destroying storms. Are you worried about the future?

VC: Change is coming down the pipe, of that much we can all be sure. But that’s not to say all these characters dread the future. The apocalypse loops back to the "late Victorian." An era of order giving way to era of chaos. All these safe, bourgeois institutions we’ve built can’t save us from what’s about to happen. Some of these characters are too comfortable, and so the threat is enormous. Other characters see the coming storm as transformative in a positive way. One of the characters, hemmed in by order, relishes the opportunity to just bleed everywhere. Myself, I think I’ve felt each of those feelings.

Monday, 28 March 2016

Flash Interview #11—Michael Prior

Michael Prior's poems have appeared in many publications across North America and the UK. His prizes include The Walrus Poetry Prize, Matrix Magazine's LitPop Award, Grain's Short Grain Contest, Magma Poetry's Editors' Prize and Vallum’s Poetry Prize. Prior currently resides in Ithaca, New York, where he is an MFA candidate in poetry at Cornell University. Model Disciple, his first book, was published this month by Vehicule Press.

Carmine Starnino: At one point in "Tashme"—the final poem in Model Disciple—your grandfather asks: "You aren't going / to put everything in the poem, are you?" Do you believe there are certain things that are better off not being included in poems?

Michael Prior: I do. I think a poem is, in an important sense, defined by its silences—whether or not something warrants being included or excluded depends entirely on the context of the individual poem, its configuration of speaker, reader, and writer. But I’m guessing, in particular, you mean to ask about the use of biographical details that when published might prove embarrassing or painful for the poet and others. With “Tashme,” a poem that has an undeniable familial resonance, I really struggled with what it meant to write about the road trip, while doing my best to be aware of my own narrativization of it, trying to resist the appropriations that might (and perhaps do) occur. So, the poem is filled with silences: there are misremembrances, there are miscommunications, there are things that can only be said by not being said. Ultimately, the poem elides certain moments and thoughts because they either seemed unhelpful to the poem as a whole, or I felt they might be too painful for my grandfather to encounter in print. His truths and his understandings obviously do not always align with mine and that’s an important thing to acknowledge. I wanted to write the best poem I could— for it to be emotionally raw and compelling—but I decided early on that even though “Tashme” moves through historical loss and hurt, it was going to be a poem primarily anchored by love. I made choices accordingly. It was the poem I could write when I wrote it: If I were to re-compose it now, or later, I’m not sure how it might differ in its omissions and inclusions.

CS: What are the challenges of writing in blank verse?

MP: There are many challenges, but also some great rewards. For a few of the poems in the book, including “Tashme,” the sort of meditativeness and movement that often occurs within blank verse felt especially important. As well, I was interested in the associative baggage that many of us bring to an inherited form and what can be done by working/playing with a form that calls attention to itself and its lineage so readily. Any devoted prosodist trying to scan the lines in “Tashme” will find they are often only ghosted by the iambic pulse, usually falling closer to something like syllabic metre—this is an intentional sort of internal tension that took a while to find my way to. While writing the poem, I began to think of its idiosyncratic “blank verse” as analogous to the curving highway which the speaker and his grandfather have to not only drive along, but also make frequent detours from, in order to find what they think they’re looking for. On a technical level, the poem went through many revisions, eventually being pared down from over twenty five pages to nineteen; it took a lot of re-reading and then forgetting other poems to find the headspace where I could write it.

CS: The book includes poems about cuttlefish, salmon and hermit crabs. Are there animals you wish you had written about?

MP: Walruses, Quokkas, and Corgis!

Labels:

Flash Interview,

Michael Prior,

Model Disciple

Sunday, 27 March 2016

Boom Times

Greeks, writes Karen Van Dyck, have been living through hunger, unemployment, electricity and water shortages and shuttered businesses. But one part of their society appears to be flourishing: poetry.

Poets writing graffiti on walls, poets reading in public squares, theatres and empty lots, poets performing in slams, chanting slogans, and singing songs at rallies, poets blogging and posting on the internet, poets teaming up with artists and musicians, teaching workshops to school children and migrants. In all of the misery and mess, new poetry is everywhere, too large and various a body of writing to fit neatly on either side of any ideological rift. Even with bookshops closing and publishers unsure of paper supplies, poets are getting their poems out there. Established literary magazines are flourishing; small presses and new periodicals abound. And if poetry production is defying economic recession, it is also overleaping the divisions of nation, class and gender. Not since the Greek military junta, known as the Colonels’ Dictatorship, in the early 1970s, when poets such as Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke, Jenny Mastoraki and Pavlina Pampoudi first appeared, has there been such an abundance of poetry being written. Indeed, the historical affinity does not stop there: it is those same poets who are doing the lion’s share of mentoring in the new generation.

Widening Gyre

Nick Tabor calls Yeats' “The Second Coming” the "most thoroughly pillaged piece of literature in English":

Since Chinua Achebe cribbed Yeats’s lines for Things Fall Apart in 1958 and Joan Didion for Slouching Towards Bethlehem a decade later, dozens if not hundreds of others have followed suit, in mediums ranging from CD-ROM games to heavy-metal albums to pornography. These references have created a feedback loop, leading ever more writers to draw from the poem for inspiration.He has a theory as to why the poem is so pillagable:

Yeats’s lines work outside their context because the word pairings are brilliant in and of themselves. “Blank and pitiless as the sun,” “stony sleep,” “vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle”—they’re both jarring and sonorous. Even “slouching towards,” probably the most overused phrase of them all, retains its ominousness after all this repetition. We’d expect the rough beast to “plod,” like a limping monster in a horror movie or the killer in No Country for Old Men (which itself, of course, takes its title from another of Yeats’s lines, in “Sailing to Byzantium”). But plodding is a conscious action; slouching is not. We can’t even tell whether the beast has a will of its own. The verb heightens the mystery and dread.

Sunday Poem

TAMAGOTCHI

Electric phoenix, temperamental pet:

Cradled by pockets, it would die unseen

While crosses and gravestones darkened the screen.

If you practiced, your love could be reset.

Shell of appetite, of family, of rest.

Its sheen wore off beneath your anxious touch:

Proof of a lie you later proved auspice,

When you wished for nights you might still reset.

Mom said it’s not your fault, you did your best:

The same condolence with which she’d lament

The hamsters starved, the goldfish overfed.

You learned on your own what can’t be reset.

By Michael Prior, from Model Disciple (Signal Editions, 2016)

Labels:

Michael Prior,

Model Disciple,

Signal Editions

Sunday, 20 March 2016

Wondrous Intellectual Height

Philip Lanthier tries to define why D.G. Jones' poetry was so unique:

Poems, wrote Jones, have backbones. They are “stalks of syntax” on which sway flocks of images “which rise and whirl / shifting / like the red-wings in their single cloud then “arrow into statement.” His poems have a wondrous intellectual height: images and perceptions drop, phrase by phrase, down the page in cryptic or ironic notation. From US poets Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams he learned how to construct an image, how to use the white spaces between lines, and how to apply an intense focus on objects as a way of compressing and communicating feeling. For Jones—to use one of his own lines—“Everywhere some small design erupts.” He discovered a kindred soul in Quebec poet Paul-Marie Lapointe, whose poems he translated. When he describes a Lapointe poem as “a series of luminous tracks that betray invisible electrons startled from atomic sleep,” he could be explaining the way his own poetry moves elliptically and unpredictably towards an indeterminate destination.

Do We Still Believe in Literary Geniuses?

If one were to shout the question “who is a literary genius?” in the general direction of a gaggle of young men in Warby Parker glasses and Chuck Taylor sneakers, the air would likely resound with shouts of “David Foster Wallace!” much to the chagrin of Jonathan Franzen, should he skulk within earshot. But what is meant by the term genius? And how much longer will it be with us? The term, after all, sits more easily with the Romantic poet in his garret than with the writer of our moment, recycling found text on her Twitter account, and thinkers and artists from Walter Benjamin to Damien Hirst have sought to consign the term to the dustbin of critical history. Indeed, should you punch the word into Google’s ngram viewer, you’ll see a slow decline in frequency of usage since 1800, with a steepish drop between 1970 and 1980 before a more recent leveling off. One wonders, then: does genius have a future in our understanding of literature? Or is the genius to be taken to Roland Barthes’ graveyard and buried in state, next to his less-distinguished peer, the author?

Sunday Poem

REGATHERING

I searched everywhere in the back-

scapes of my life—through the backlogged paperwork,

the back of the topmost cupboard, the backs of old books—

to find my heart. I think I lost it

this time last year. I’d given up on it all. Allowed

mortality to piggyback onto everything, blowing the roof off what

I’d built. Why try, I thought? And here

the computer exacted an ounce of my heart,

and there a drink in the afternoon took some of it; the lion’s

share was carved up by sleep and meted

to the various wishes my body made

when I wasn’t around. My heart was scattered. It would be

near impossible to gather it all back. Michelle watched

as I travelled the apartment like a streetcar at night—as vacant

and vulgarly lit.

She hugged me to bed, cupped her life,

her workaday problems around mine and held them aloft. She sung

such elegant music. I searched the back-scapes,

thinking the shards of my heart would have dumbly

fallen somewhere. I tried to find it, actually, because

there have been a few deaths around me recently

and I could really use my heart. I did find it, too. Quite

by accident. I’d given up on getting it back, when I crawled

into bed and Michelle flung a half-asleep arm

around me. And there it was, gathered. I have to give

the little bastard credit, my heart, it knows how to get home.

By Vincent Colistro, from Late Victorians (Signal Editions, 2016)

Labels:

Signal Editions,

Sunday Poem,

Vincent Colistro

Sunday, 6 March 2016

Sunday Poem

THE LOVE SONG OF J. ACER TRAVELMATE

Come. Dressed for a honeymoon. Like a mango

sculpted to a blossom, impaled. Learn to tango

because it’s a damn good investment. Be strong

as a rubber. For you, every lover will be wrong.

Don the hubris of a blonde. Cavort like a brunette.

Anticipate the Russian in the spin of chat roulette.

Accept ennui, Bleu Nuit, double Texas hold ‘em.

Give in absolutely to the carpal tunnel syndrome.

Because insomnia isn’t just a marketing strategy.

Buy the decaffeinated bottle of Five-hour Energy.

Forget cyborg, sybian, Berkley Horse and Trojan.

Because one curiously clumsy click hurts no one.

In every phallic object, the symbol is clear-cut:

silicone conifer, hairy hardwood, leather chestnut.

Crave this apotheosis of a plastic prosthesis.

Because. Because. Because. Because. Because.

Because of the wonderful things it does. Follow

the email migration of the chain mail manifesto.

Be a Pay Pal. Pop your Paxil. Spatter melted candle.

Train your brain to feel nerve endings in a pixel.

Stretch your skin on webcam. Be an austere host.

Because you are bound by the mouse to the bedpost.

By Daniel Renton, from Milk Teeth (Frog Hollow Press, 2016)

Saturday, 5 March 2016

Worthy of Attention

Arguing that to "transition from awareness of inequality to outcomes that address that inequality, attention must be paid," critic Eva Jurczyk has decided to only review books written by women:

This wouldn’t change the number of books by women that are published every year, nor the total number of books that Publisher’s Weekly reviews—some eight thousand per year, mostly for librarians, the media, and booksellers—but if someone is reserving all of their mental energy and all of their ink for female-authored books, then perhaps these books will be covered sooner, the gems among them celebrated louder, and the publishing industry will slowly adjust the definition of the type of book that is deemed worthy of attention.

She continues:

The books written by men will still get covered, just not by me—the female-written books, some of which might otherwise have had to wait months post-publication for a printed review, will be my top priority. I’m still going to read books by male authors—but rather than call dibs on the review copy, I’ll put them on hold at the library. I don’t expect that reviewing fewer pirate books and more female-authored books will change the publishing industry, just like I don’t expect a hashtag or VIDA counts to upend hundreds of years of ingrained inequity, but lots of small decisions made by lots of individuals might add up to something.(Illustration by Hannah Wilson)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)