James Langer and Mark Callanan discuss their new anthology The Breakwater Book of Contemporary Newfoundland Poetry.

Breaking news. Literary exhortation. Entertainments. And occasionally the arcane.

Monday, 29 April 2013

Verbatim

"Maybe the epic poet of Newfoundland has yet to be discovered. She may be out there contemplating sending her first suite of poems off to a literary journal. She may be thinking about taking a creative writing class or may just be now reading the poet that will change her life and draw her to poetry. I’d like to think that she’s the person this anthology was compiled for. A little message in a time capsule that reads, 'Here is your inheritance. Now carry on.'"

James Langer and Mark Callanan discuss their new anthology The Breakwater Book of Contemporary Newfoundland Poetry.

James Langer and Mark Callanan discuss their new anthology The Breakwater Book of Contemporary Newfoundland Poetry.

Sunday, 28 April 2013

Sunday Poem

SAD LOG!

Triste Lignum!—Horace

Branches like a Bacchic dancer thrashed

Ever more furious and faster

Through the storm, then catastrophically crashed

Into my window, not the last disaster

But a mere mishap that may be mended.

No mere cataclysm ever ended

The war of winds, the travail of the trees

As they changed from ghastly green to grubby brown

Till, secretly subverted by disease,

They trembled to their roots and tumbled down,

As I shall do, one long-awaited day

When whatever wind will carry me away.

From Reliquary and Other Poems by Daryl Hine (Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 2013)

Ahead of Their Time

Amit Majmudar has unburied masterpieces by Matthew Arnold, Lord Byron and Tennyson where no one ever thought to look—including the poets themselves.

Some traits that we value in poetry—irregularity of rhythm, unpredictability of language, a highly personal bent—were things that the Victorians allowed themselves only in their letters. The letter also lent itself to a structural characteristic so ubiquitous in contemporary poems it is almost unrecognized: the first-person anecdote. So Matthew Arnold is terribly out of favor among contemporary poets; I myself find much of his poetry unreadable. But what a shock in the Letters!According to Benjamin Schwarz, it would take another two decades after Tennyson's death for someone to anticipate Majmudar's insight:

Frost, who urged Thomas to turn to poetry, proposed that he transform into poems some segments from his finely observed book on country life In Pursuit of Spring—a decisive suggestion. “All he ever got from me,” Frost said years later, “was admiration for the poet in him before he had written a line of poetry.” Thomas would, shortly before his death, characterize his poems as the “quintessences of the best parts of my prose books.”

Friday, 26 April 2013

Thursday, 25 April 2013

Can Twitter Make You A Better Poet?

I was always meticulous about individual lines, but having to make them stand on their own made me think about their function on a whole new level. Every time I post a tweet I ask to myself “is this musically cohesive?” “Does it resonate content-wise without its context?” and most importantly, “Does it give the reader something more than what’s contained in its 140 characters?” This last consideration is what’s really improved how I approach writing. I don’t want these tweets to be clever little quips, or single thoughts that make a person sigh or chuckle. I want them to open infinitely off the edges of the page, or screen, so that each new tweet is the key to its own, much larger universe. Alice Munro is brilliant at this: in a single gesture or off-handed comment her characters inflate before the reader’s eyes, becoming fully realized within those few strokes. Poetry, if anything, should do the same in even fewer strokes.

Wednesday, 24 April 2013

Patchwork Poetry

Working with Mary Dalton on her new collection, Hooking, brought into sharp relief how little I knew about the cento. Over at Oona, a blogger makes a case for the form's cultural relevance:

In an age of sampling, remixes, & flarf, the renaissance of the cento, a form that dates, one way or another, at least to ancient Greece, is oddly apt. The possibilities of this kind of poetic collage are dizzying.Marie Okáčová zooms in:

I believe that the cento, rather than being an eccentric curiosity devoid of all literary value, is primarily a kind of intricate and actually perfectly legitimate play with language, which reflects its principles of operation. Being in fact the embodiment of absolute intertextuality, the patchwork poems implicitly question every notion of literary originality because they emphasize the interdepenence of individual texts representing different literary meta-languages. The cento is therefore "recycled" art only in a more conspicuous way than the rest of literature inevitably is; this, however, does not mean that a work of literature can actually never be original and inventive. In fact, as an example of intertextuality par excellence, the patchwork poetry is, at least conceptually, a highly innovative literary form.

Labels:

cento,

flarf,

Hooking,

Marie Okáčová,

Mary Dalton,

Newfoundland poetry,

Oona,

remix,

Signal Editions

Monday, 22 April 2013

Sunday, 21 April 2013

Sunday Poem

DEATH TRAPS

A big woods loop of solitude and freshness.

Killarney’s ambled roaming and balsam-smell—

the sought. Days one through three, settled in and dirtied.

The fourth and fifth, sopping, famished. Six, distrust in nature.

Seven through ten, worst-case imaginings:

better to hike the rescue, or wait, hurt?

Play-acting at self-sufficiency:

yes, can pump water, but no, couldn’t tourniquet.

Ultra-liters, and three black bears—

the only passersby.

Miles of wild blueberries: what I’d been after.

After me: moss’ treachery underfoot.

Asked before departure: the near north’s forested quiet.

The reassessed goal: re-reaching others.

Fewer all-nighters of star-canopied joints—

more early-to-beds and held urine.

Less like ferns and boulders, more like death traps—

forecasting the fallout, should head and rock meet.

From The Grey Tote (Signal Editions, 2013) by Deena Kara Shaffer.

Saturday, 20 April 2013

Expeditions into the Interior

Anthony Madrid comes up with a cool idea:

There should be a magazine called Expeditions into the Interior, and the way it would work would be for people to accept assignments to report on all these old books of poetry that nobody wants to read but which might have good shit in ’em. For example, Melville’s Clarel. Who’s gonna read that. Nobody. But what if I was gonna give you fifty bucks. We’ll give you fifty to read it and write about it in fluent Caveman. All you gotta do is say what you saw. Point to some good lines. That’s it. But. If you accept the assignment and you don’t write anything? Yeah, that’s a $100 penalty. This is how we’re gonna pay our responsible writers. It’s also how we’re gonna finally find out if there’s anything in John Gay’s Fables. Or in the Thebiad. Or just all that stuff.

Labels:

Anthony Madrid,

Melville,

Poetry Foundation

Thursday, 18 April 2013

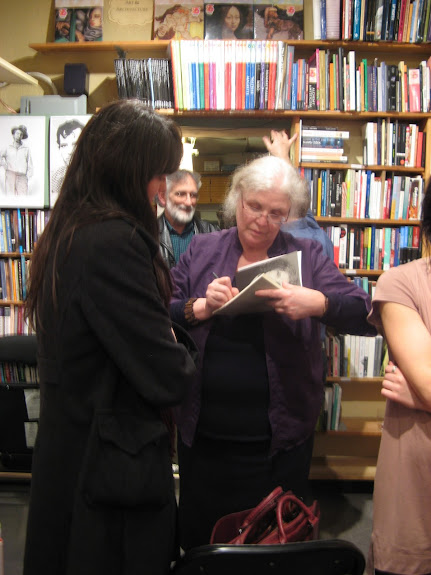

Hooking

Mary Dalton's collection of centos, Hooking, arrived in the office yesterday. She launches her book tonight in Montreal at Argo (with special guest Sue Sinclair). She reads in Ottawa on April 23 and Toronto on April 24. In an interview with John Barton, she explains the notion of authorship underlying the book:

I think of the lines I’ve excised from poems as material, as strips of words. Each line, the hooking of these words into this particular sequence on a line, is the creation of its individual author; the sum of the lines in each cento, the way in which these syntactical fragments have been hooked together, is my creation. These pieces are at once mine and not mine. They give rise to the question, where does originality lie?

Labels:

Argo Bookstore,

cento,

Hooking,

Mary Dalton,

Sue Sinclair

Wednesday, 17 April 2013

Tuesday, 16 April 2013

Flunked

Using the Finkbeiner Test—created to suss out gender bias in profiles of female scientists—Melissa Dalgleish discovers that Canadian poets don't fare any better:

The title of Sandra Martin's piece was the first red flag: "The nurturing nature of Jay Macpherson." No mention of her brilliant poetic mind, her many awards, or Martin's own newspaper's statement, back in 1957, that Macpherson was Canada's "finest young poet." Indeed, no mention of the fact that Macpherson was a poet at all. Despite Macpherson's choice to remain unmarried and childless, Martin still manages to construct an image of her as maternal which trumps her professional identity, suggesting that her poetic output was small because "she was a ministering angel to waifs and strays, often to the detriment of her own work and health."

Monday, 15 April 2013

Just Rewards

Sharon Olds was awarded the Pulitzer Prize today for her poetry collection Stag's Leap. It seems like a fine time to point readers to Tony Hoagland's great essay from 2009 defending her work.

What do you get as a reward for being a poet like Sharon Olds? For having written five hundred-plus poems which plumb the range of family dynamics and intimate physicality with a precision and metaphorical resourcefulness greater than may have ever before been applied to those subjects? For having permanently extended and transformed the tradition of the domestic poem? For doing as much, singlehandedly, to win readers to American poetry, as any poet of the latter 20th century? For making poetry seem vital and relevant to young and not-so-young adults all over the place? Well, you win great popularity. You are loved by many, for both right and wrong reasons. You are run down by envious peers, and overlooked by academics. Your name is invoked like a brand name to denote the obviousness of confessional poetry. You are accused of repetition, narcissism, and exhibitionism.

Labels:

Pulitzer Prize,

Sharon Olds,

Stag's Leap,

Tony Hoagland

Sunday, 14 April 2013

Sunday Poem

CLONE

Four should be enough of me for me. No, three.

They might not easily apprehend, but they can do,

and doing’s the battle I get them to attend.

To send them out with grocery lists and day-to-days;

milk, bread, whatever I yen for between bread, they’ll even

plate it carefully so I can keep on teasing out this stuff.

Parties, several at once, they drink like cops

filling late-month quotas, engage the feckless

literati with The Phaedrus while I seduce their wives.

That means course enrolment. Tuition. Tough;

I learn to play guitar unburdened during

their job interviews. Finally fangle origami.

It’s a bit like being God, seeing myself from behind,

askance in the way you can’t but want to. The sum

of our actions define me while they live my lives

as though committing crimes. Lately we don’t look

each other in the eye. They’re not reading dictionaries

in the off hours. Unfashionably late, on the skive

at the local, making fools of me. Unviable.

Soon and earlier than they think, with such retrograde

expectancy, they’ll drown in the last air left them.

So it’s a waiting game. Time for a fresh start; tonight

I’ll hit the town and rake the coals they’ve burned. I am

going to wear my favourite shirt, the brown one. Or am I.

From For Display Purposes Only (Coach House, 2013) by David Seymour.

Saturday, 13 April 2013

A Saving Mutiny

Spurred by Helen Vendler's chapter on Alexander Pope that appears in her book Poets Thinking, Timothy Donnelly unpacks Vendler's notion of "quasi-intelligibility":

For as long as I can remember I’ve been sensitive to the distance between an object of thought or perception and any given way of expressing it, knowing that the most efficient, utile, or commonplace way of putting it might be appropriate for the daytime, so to speak, or in the marketplace, but at night, and in the forest, all bets were off—or else they should be. A sharpened pencil might become “a stick of gold with lead in it, excited to a point.” A glass of ice water might transform into “a liquid clearness contained in a slower liquid clearness, interrupted by solids of the first clearness.” And somehow, sometimes, to re-conceive the near-at-hand in a way surpassing that in which routine and its dry tongue compels one to experience it has seemed like more than just recreation or refreshment—it has felt like a necessary refusal, a saving mutiny.

Thursday, 11 April 2013

Storming the Castle?

David Biespiel is unimpressed by the now-infamous Kenneth Goldsmith tweet.

Our finest postmodernists have turned into purists and party base delegates. And that’s where things just get sad. The vigor and joy with which our best postmodernists attack any criticism of their aesthetic has all the hallmarks of the apparatchik.

He continues:

By adopting and tweeting the semantics of political shorthand for literary criticism (i.e., attacking Ange Mlinko as a ‘conservative’), it’s made the whole postmodernist movement jump the shark. This week Postmodern poetics is looking a lot like the Fonz in a leather jacket on skis.

Labels:

Ange Mlinko,

David Biespiel,

Kenneth Goldsmith

Wednesday, 10 April 2013

Breaking Bad

A frustrated David Yezzi—who compares today's verse to "a spayed housecat lolling in a warm patch of sun"—wants poets to stop playing it safe:

How did the main effects of poetry ever boil down to these: the genial revelation, the sweetly poignant middle-aged lament, the winsome ode to the suburban soul? The problem is that such poems lie: no one in the suburbs is that bland; no reasonable person reaches middle age with so little outrage at life’s absurdities. What an excruciating world contemporary poetry describes: one in which everyone is either ironic, on the one hand, or enlightened and kind on the other—not to mention selfless, wise, and caring. Even tragic or horrible events provoke only pre-approved feelings. Poetry of this ilk has a sentimental, idealizing bent; it’s high-minded and “evolved.” Like all utopias, the world it presents exists nowhere. Some might argue that poetry should elevate, showing people at their best, each of us aspiring to forgive foibles with patience and understanding. But that kind of poetry amounts to little more than a fairy tale, a condescending sop to our own vanity.

Tuesday, 9 April 2013

Sunday, 7 April 2013

Sunday Poem

AMMONITE

Jeweller’s saw bisects the whorl.

Heart surgery. Chambers crack.

I am going sane all the sudden.

Arteries are bright with oxygen

saw-teeth coax open the ammonitella

collarbones butterfly

valves unite as phragmocones

waves of disconcerting bliss

crystal, fossil, this, now. Open.

From Whirr & Click (2013) by Micheline Maylor

Labels:

Micheline Maylor,

Sunday Poem,

Whirr and Click

Saturday, 6 April 2013

Poseur Alert

"Boy oh boy. It's really scary to see how conservative poet Ange Mlinko has become. She used to be one of us."

Kenneth Goldsmith exposes the group-think the avant-garde are always at pains to deny, and confirms what "conservative" critics everywhere know to be their only sin: independent thought.

Labels:

Ange Mlinko,

Kenneth Goldsmith,

Poseur Alert

Women's Poetry

Lisa Russ Spaar, Aracelis Girmay and Daisy Fried (pictured above) tackle the issue of gender in poetry in a candid, thought-provoking exchange, Here's a moment I like, from Fried:

Like any poet writing in any mode, I make hundreds of formal choices in every poem. Syntax, lineation, tone, pacing, voice, deployment of image: these are all formal choices. They’re all opportunities for thinking in certain ways and at certain rates. Likewise, traditional form is an opportunity, not a vessel to be filled up. I can’t imagine considering any of this in terms of gender. I really can’t get my brain around that concept. I realize there’s theory about female ways of thinking and male ways of thinking, female language and male language. If they’re true—I’m skeptical—I’m politically opposed to acting as if they’re true. The minute you start assigning gender to certain formal choices or gestures or tics, you have to start pointing out the million exceptions.

Labels:

Aracelis Girmay,

Boston Review,

CWILA,

Daisy Fried,

Lisa Russ Spaar,

VIDA

Friday, 5 April 2013

Official Avant-Garde Culture

In his bracing 6200-word dismantling of Charles Bernstein's career, Jason Guriel takes a minute to ask a few questions:

How does a Language poet know when her poem is finished, or at least ready for the typesetter? (It strikes me that a non-linear and non-representational poetry of fragments that resist closure could go on forever.) Does a Language poem end where it does because its author got winded and, well, a poem has to end somewhere? What does her revision process look like? Why is it “Surfeit, sure fight,” and not “Sure fight, surfeit”? Why couldn’t the lines in “Solidarity Is the Name We Give to What We Cannot Hold” and “Let’s Just Say” be shuffled into a different order and still enable the reader to come up with the same point about the wobbliness of words? And if the lines can be shuffled into a different order, why should the reader read the poems at all? And why does the Language poet keep writing them, once she’s got a few under her belt? How many Language poems does it take to unscrew the signified from the signifier?(Drawing from "Mini Gross Sketches")

Pollock Replies

Immensely gratified as I am by Stewart Cole's thoughtful and sensitive review, I'm puzzled by his critique on these points. On "the work of art per se": the whole thrust of the essay he quotes that phrase from ("The Art of Poetry") is to greatly expand the reach of my own thinking about poetry to include pragmatic, mimetic and performative values. Early in the essay I write that "to ignore all other values besides the aesthetic would be to miss a great deal of what a lot of poetry does." And by the end of the essay I say things like this: "[The] object [of truly great poetry] is ultimately the formation, and transformation, of the human self and community." Granted, I argue that aesthetic value must be central to any good theory of poetry. But my position is much broader than Cole gives me credit for here.

On the matter of our aesthetic sensitivities being affected by our material conditions: of course they are, but I'd argue that we shouldn't merely surrender to our own social conditioning; we should strive to overcome it. That's what it means to be a true cosmopolitan. As I say later in the same essay, "particular aesthetic values change over time: some eras and readers will especially value classical clarity and restraint, others romantic passion or intellectual challenge; but in our time it should be possible to value a wide range of aesthetic qualities, because we have the benefit of a vast literary history. I can value Lorca's fierce rhetorical passion and surreal imagery, and also Cavafy's classical restraint and clarity; nevertheless I can also value Lorca over some minor French surrealist and Cavafy over some dull author of versified history. It is not the poet's particular aesthetic values that should determine the critic's estimation of the poem, but the quality of the art."—James Pollock

Thursday, 4 April 2013

You Are Here

Let me make my position on this clear: there is no “work of art per se,” in the sense that “per se” means in itself and so implies that a work of art that can in any way be isolated from the social conditions of its creation and/or reception. Such a notion—also embodied in Pollock’s conception of poetry as “an autonomous technology for producing aesthetic pleasure”—is a bourgeois chimera.Cole continues:

In other words, what qualifies for us as “delight, originality, and imagination,” or which aspects of “verbal sensitivity and dexterity” we are most attuned to as any given person in any given time is significantly shaped by the political, social, and otherwise material conditions that produce both us and the art we encounter. This is why the best argument in favour of formalist practice remains a social one: that such practice does justice to poetry’s social origins and orientation, linking us rhythmically and rhetorically to a shared past and giving shape to our aspirations for communal futures. This is also why the most compelling argument advanced by the ‘innovative’ school against such formalisms is also precisely social: that the old forms stand at odds with our modern social formations, that we must seek out new forms to reflect our societal disorientation. These two positions might best be thought of as the two ends of a continuum, somewhere along which—whether they know it or not—most poets today situate their practice.

Wednesday, 3 April 2013

Tuesday, 2 April 2013

Infinite Feedback Loop

Lazy Bastardism was reviewed alongside new books by Glyn Maxwell and Mary Ruefle in the April issue of Poetry magazine. The conversation—held between Michael Lista, Ange Mlinko and Gwyneth Lewis—is utterly satisfying (and at times, for me, blush-inducing). One of the most interesting exchanges occurred over a few lines by Robyn Sarah that Mlinko first encountered in my book. Disappointed that Maxwell doesn't spend more time on the nuts-and-bolts of how metaphors are put together, Mlinko brings up Sarah:

Michael Lista's reply:To take as an example the lines I quoted from Robyn Sarah, was I really drawn to them because of the versification?at the back of the palate

the ghost of a rose

in the core of the carrot.Well, I admit, the anapest-ish bounce of those lines has something to do with their memorability, and the palate/carrot rhyme is indispensable, but the real achievement here is the oxymoronic yoking of the rose and the carrot (smell vs. taste; sweet vs. bitter; pretty vs. nutritive; pink vs. orange). Oxymoronic, but surprisingly true — I taste that rose now in raw carrots, indelibly. I think Maxwell would wager that the lightning-strike freshness of metaphor arose organically (no pun intended) from the modulation of the vowels and the fatedness of the rhyme. And there is a lot of truth to the idea that versification is a poetic machinery by which you find yourself saying smarter things than you would have otherwise (to paraphrase James Merrill). But I could just as easily posit that Sarah was actually cutting the top off a carrot, saw the radial symmetry of its core, glimpsed (at a lightning stroke) the visual rhyme with a rose, and constructed the musical lines to be the best container for this metaphor.

I do think we’re drawn to the Sarah lines in large part because of the versification — it’s itself metaphoric. Yes, the “anapest-ish” bounce is part of it, but so too is the circularity and symmetry of (to use words Maxwell dislikes) the assonance and consonance (at, back, palate/ghost, rose/core, carrot) and that lovely slant rhyme of “palate” and “carrot.” The total effect is to give the aural, synesthetic impression of both the cross-cut carrot and the spiraled petals of a rose. The metaphor is itself contained within a mnemonic metaphor, which makes forgetting the lines next to impossible. Today both bad free verse and bad formalism disappoint for the same reason: the form has been divorced from its metaphor. In the case of bad free verse, the form feels arbitrarily default, like a font. With bad formalism, it feels willfully decorative, like a font. When poems of each kind succeed, it’s because their containers — poetry is the only art form that is its own container — are constructed out of the materials of their contents, in a kind of infinite feedback loop.

Play It By Ear

John McAuliffe isn't entirely convinced by Paul Muldoon's foray into song-writing:

Rock lyrics, though, are far more confining and precast, formally, than the expansive long rhymed poems and brilliant sonnets and sequences of Muldoon’s poetry. At times a reader can almost hear the sounds of Muldoon’s wheels spinning as he attempts to drive the lyrics towards the territory of his poems.Matthrew Zapruder reminds us of the difference between poems and song lyrics:

Words in a poem take place against the context of silence (or maybe an espresso maker, depending on the reading series), whereas, as musicians like Will Oldham and David Byrne have recently pointed out, lyrics take place in the context of a lot of deliberate musical information: melody, rhythm, instrumentation, the quality of the singer’'s voice, other qualities of the recording, etc. Without all that musical information, lyrics usually do not function as well, precisely because they were intentionally designed that way. The ways the conditions of that environment affect the construction of the words (refrain, repetition, the ways information that can be communicated musically must be communicated in other ways in a poem, etc.) is where we can begin to locate the main differences between poetry and lyrics.

Monday, 1 April 2013

Verbatim

"No, no, not at all. No, stupidity has got nothing to do with it. It’s simply an activity which has been a little overestimated and is regarded as something of major importance. Personally, I don’t believe it is all it’s cracked up to be. It’s one of those human activities that is not crucially important."

Marcel Duchamp comes clean on his feelings about painting.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)

.JPG)