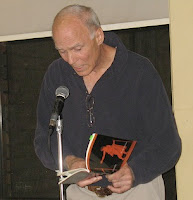

[Don Coles is the author of ten books of poetry and the novel Doctor Bloom's Story. He won the Governor General's Award for Poetry in 1993 for Forests of the Medieval World and the Trillium prize in 2000 for Kurgan. Formerly a professor at York University, he lives in Toronto

[Don Coles is the author of ten books of poetry and the novel Doctor Bloom's Story. He won the Governor General's Award for Poetry in 1993 for Forests of the Medieval World and the Trillium prize in 2000 for Kurgan. Formerly a professor at York University, he lives in Toronto.

Every Wednesday for the next two months, we'll post an entry by Coles taken from his 2007 book of essays and reviews, Dropped Glove in Regent Street: An Autobiography by Other Means ]This is the sad story of myself grown old, a condition I did not strive after. Keats, Rimbaud, Plath (only one of whom I actually met) all demonstrate the value of an early departure—who wants to be the crazy old Ruskin or the rambling octogenarian Wordsworth or even the merely shaky May Sarton? And yet here I am, threescore-and-ten-plus, nobody can call me anything other than old and people have stopped trying.

Best, then, is to do as I do, don neutral-coloured clothing and stand at the fringes of whatever comes your way; no one is likely to ask your opinion or thrust a microphone at you anyway, they have more attractive options…and who blames them?

What makes me smile, nevertheless, a mirthless smile it goes without saying, is remembering, even as I step unresentfully back whenever some younger person wishes to stand where I am standing, how there was a time when…yes, reader, here it comes. When I was young! When I, too, was visible on a sidewalk!

The pathos of this old fellow’s unverifiable claim, you are now thinking, and again, I cannot blame you. Pathos indeed.

And yet I will tell you, for it’s too late to turn back now, that one afternoon walking up the via Tornabuoni in Florence, aged 22 and wearing a dark raincoat on a grey day, I saw approaching me down the via Tornabuoni a gaggle of people of whom only one was truly present to my gaze, this being a tall and blonde and carelessly sumptuous in her attire woman of about 35, English I felt and feel sure, closely guarded in her walking by three diminutive middle-aged men, all credible stand-ins for Carlo Ponti.

I stared unashamedly at this wonder and had a fleeting impression that she briefly returned my look just as the four of them left the sidewalk along which they had been approaching me, crossed the road, and disappeared into Doney’s Bar, a toney place halfway up the Tornabuoni and one I had never entered.

I stopped to watch them enter Doney’s Bar, feeling a formless lament, but feeling, also, not quite ready to start up walking again. So I loitered, I remember there was a florist’s where I was standing and I occasionally looked at a plant or two while I stood there. I have never had any interest in plants. It was then that the first of my two shameful and unforgiven acts—non-acts, as you will see—took place.

Because as I stood beside the florist’s window the blonde woman, unaccompanied now by any of the Carlo Ponti look-alikes, reappeared at Doney’s door and gazed directly across the street at me.

At me? This couldn’t be, I at once felt. I looked back at the florist’s window, someone must surely be signaling to her from within, desperately waving a bouquet of violets. But no, nothing moved within, no one appeared, there was only one person on the street and it was I. The woman was still standing there, gazing across. The Tornabuoni held its breath.

It had held its breath thousands of times before but at the moment this didn’t concern me. The woman said nothing, merely waited and looked. What was she supposed to do, wave? She had done her share, she had done all she could, I knew this. It was my turn, some signal, a quick run across the street, the exchange of a few words, a rendezvous, where, anywhere, down there by the Arno, in an hour, who cared, anything at all. I didn’t budge.

I did and said nothing.

Why not, didn’t I trust this? Here was the lustrous heroine of The Sun Also Rises, Lady Brett, her ancestral meadows spreading endlessly about her as obviously as the green curtains on Doney’s windows, and I was a stone. She looked, she waited a few more seconds, she turned and re-entered the bar. Thinking whatever she was thinking. And I—? Walked on my way, towards whatever exotic appointment awaited me. Picking up a reserved book at the American library, probably.

It gets worse. Some months later, back in London after my student year in Florence, walking up Regent Street on a pre-Christmas day, a few snowflakes testing the air, passing Austin Reed’s long storefront I noticed a small queue of people waiting at the bus stop. I wasn’t intent on catching a bus so I paid no attention, I merely continued to approach them. As I was in the act of passing them, something fell to the sidewalk just before my step. I paused, it was a woman’s glove.

I looked to see who had dropped it—the sky opened and fell upon me. It was Lady Brett. The blonde from the Via Tornbuoni. Beyond any doubt. Our eyes met. We were so close we could have embraced without moving anything but our arms. Across the road was the Café Royale, celebrated rendezvous of Waugh, Orwell, Connolly, heroes all: a place with small tables in tactfully positioned alcoves and the discreetest of waiters. You will not believe what happened next.

I did not pick up the glove. I paused, I didn’t want to step on it, after all. For a second or two it waited there. Then she bent to pick it up. I walked grotesquely on. Seconds later the bus arrived, and the queue, certainly including her, got on it. It rolled up Regent Street past me.

At this point I was almost staggering. Drowning in self-contempt. I tried to assure myself that we must meet again, surely this would happen, after all we had now had two meetings in a half-year, it must be fated, I would perhaps see her tomorrow, perhaps at this same bus stop. And never again would I fail her.

I was at that same bus stop at the same hour the next day, needless to say she was not. Or any other day, or on any other London or Florence street. Not that I know. Ever.

What does this have to do with old age? Nothing.

Something to do with youth, though.

(from

A Dropped Glove in Regent Street: An Autobiography by Other Means by Don Coles, 2007)

Brian Palmu, who is quietly emerging as one of the sharper poetry critics in the Canadian blogosphere (admittedly, not a big group to begin with), gives us his notes to the 83 books of poetry he read in 2008 -- that's probably 82 more than any sane, well-adjusted man should have to read.

Brian Palmu, who is quietly emerging as one of the sharper poetry critics in the Canadian blogosphere (admittedly, not a big group to begin with), gives us his notes to the 83 books of poetry he read in 2008 -- that's probably 82 more than any sane, well-adjusted man should have to read.