Over these eighteen lines, we have tried to follow the poem grammatically, descriptively, narratively, thematically, and emotionally, and in each case, we’ve found ourselves only partially equipped. After a certain place in the stream, the rocks get too far apart for us to keep our shoes dry. And falling in might offer its own pleasure, assuming the stream is a stream of water. But not only can we not imagine a particular speaker choosing to say these things out loud, we can’t even deduce from these lines any central mind that might choose to put them in a poem. This is not to say we don’t enjoy them. It’s not to say that they can’t be opportunities to reflect upon our own lives. And it’s certainly not to say that we aren’t challenged by the brokenness of the language to examine the parts and functions of language itself. We don’t bother to think about how the lamp switch works until it breaks and we have to fix it. Maybe nonsensical syntax serves the same end. Maybe Ashbery has generously given us a broken lamp switch. “So much going on here,” one’s inner workshop leader wants to say, “a lot of really fresh language,” and, “We’ve only just scratched the surface.” In other words: There must be a lot going on here, because I don’t understand a word of it, but some of the diction at least is unexpected, though God knows what it means, and anyway I don’t want to be the only one in the room who missed the brilliant political allegory, so I’ll just say we’ve only scratched the surface.

Breaking news. Literary exhortation. Entertainments. And occasionally the arcane.

Wednesday, 31 December 2014

Broken Lamp Switch Poems

Tuesday, 30 December 2014

Vowel Colour

Alex Boyd has been busy archiving content from his now defunct Northern Poetry Review mag. Some nice rediscoveries to make, including a lovely interview with Elise Partridge which includes this interesting observation:

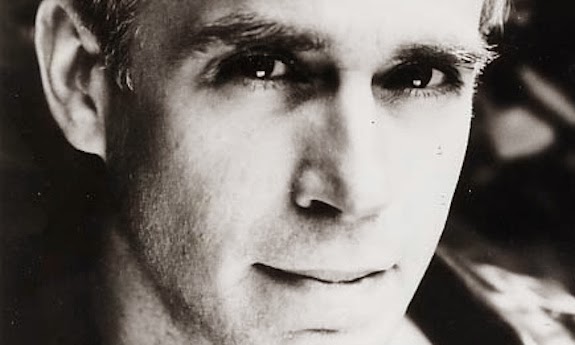

Can devices like vowel-color and so on really express meaning? There’s something inexplicable about it all, but I would certainly agree that syntax and sound can. Would the Duke in Browning’s “My Last Duchess” have such icy control of his syntax if he were despondent about his late wife, rather than angry enough to have had her murdered? If you look at the syntax and listen to the sound in sections of Tennyson’s “In Memoriam A. H. H.” or his “Now sleeps the crimson petal,” for example, you can make an argument about how vowels, consonants and syntax help convey such emotions as resignation and despair or tenderness and eager anticipation.(Photograph of Alfred Lord Tennyson)

Blinkered

Will Self is bummed out about the future of the physical book:

One thing is absolutely clear: reading on screen is fundamentally different from reading on paper, and just as solitary, silent, focused reading is a function of the physical codex, so the digital text will bring with it new forms of reading, learning, memory and even consciousness. I think this so self-evident as to scarcely require elucidation; the unwillingness of the literary community—in its broadest sense—to accept the inevitability of this transformation can only be ascribed to their being blinkered by the boards of their codices. The majority of the text currently read in the technologically advanced world is already digitised—and most of that text is accessed via internet-enabled devices. All the valorisation of the printed word—its fusty scent, its silk, its heft—is a rearguard action: the book is already in desperate, riffling retreat.

Sunday, 28 December 2014

Sunday Poem

THE TASTE OF LOSS

With the first sip of dark espresso

in the morning I think of her

how we would drink it together

and she said I always took too long

and let it go cold.

Another winter of her absence

and spring comes again without her.

A white squirrel chatters on the back porch,

last fall's pumpkin, half-gnawed, frozen there.

Azure sky above, sunlight on the snow.

From the bare lilac, a cardinal whistles,

a chickadee dee dees.

I stay in all this New Year's Eve day,

loss, the mineral salt taste in my mouth.

Turn it into a glass of ice water

I can down in one drink. I take it

in my hand, bring it to my lips, the smooth glass,

I know that burning cold, I know it.

From The Montreal Book of the Dead (Vallum Chapbook Series, 2014) by Mary di Michele

Saturday, 27 December 2014

The Grand Seduction

In his interview with me, Michael Harris explains some of his methods when editing the Signal series:

A first line literally has to have one hooked immediately. Without a first line that either leads in immediately to a second line hook or a third line hook, there isn’t any poem, you don’t get down to the fourth line usually. It has to be something that doesn’t throw one off. It has to actually bring one in. Reading a poem is a little bit like falling in love. Ten years on, if it was a correct falling-in-love you’re still with them and if it was an incorrect falling-in-love, you’re not with them anymore.

C: Does that thinking affect arrangement in a book? For example, the first poem you place in your manuscript?

M: A friend of mine, the Quebecois poet Michel Garneau, once told me, “Lead with your best piece.” And that makes a kind of sense. He is, amongst other things, an actor and a playwright. And theatrically, what’s interesting is to have something very strong at the beginning. But I don’t think the first poem in a book has to be the best poem. It has to be a poem that is absolutely solid, that doesn’t push one away, that says, “Here I am. I’m a decently written piece. I have subject matter that’s of interest. I have a couple of oddities. A couple of interesting tropes that tell you I’m an interesting poet beyond what one might normally read.” And by the end of the first page, you have to have read something of import. Then the second page and the 3rd page and the 4th page, you can fool around a bit. By the time the 5th or 6th page, then you have to have a plateau poem, a decent poem, a very good poem. Something that’s so good that, had you put it first, you might have lost the reader; it’s a little bit like getting introduced to somebody you don’t know and coming on too strong. That’s how Shakespeare managed the plays. Very seldom is the huge speech in Act 1. The magic develops slowly. By the time you get to Act 3 or 4 there’s strength, power and explosiveness.

C: You don’t want to come on too strong?

M: You want to be absolutely present and inevitable, but you can’t whack somebody over the head and say this is genius. At least, that’s how I would organize the seduction.

Saturday, 20 December 2014

My Top Ten of 2014

If we exclude the brilliant books I edited for @VehiculePress (The Scarborough by @michaellista, Satisfying Clicking Sound by @JasonGuriel,

— Carmine Starnino (@cstarnino) December 20, 2014

Dog Ear by Jim Johnstone, Radio Weather by Shoshanna Wingate) then these who be the 10 bks of Cdn poetry that give me most pleasure in 2014:

— Carmine Starnino (@cstarnino) December 20, 2014

1/ For Your Safety Please Hold On by Kayla Czaga (Nightwood) @czagazaga @NightwoodEd

— Carmine Starnino (@cstarnino) December 20, 2014

2/ Inheritance by Kerry-Lee Powell (Biblioasis) @biblioasis @kerryleepowell1

— Carmine Starnino (@cstarnino) December 20, 2014

3/^^^^^^ [Sharps] by Stevie Howell (Ice House) @steviehowl @goose_lane

— Carmine Starnino (@cstarnino) December 20, 2014

4/ Circa Nineteen Hundred and Grief by Tim Bowling (Gaspereau)

— Carmine Starnino (@cstarnino) December 20, 2014

5/ Glad and Sorry Seasons by by Catherine Chandler (Biblioasis) @biblioasis

— Carmine Starnino (@cstarnino) December 20, 2014

6/ Ringing Here & There: A Nature Calendar by Brian Bartlett (Fitzhenry & Whiteside) @FitzWhits

— Carmine Starnino (@cstarnino) December 20, 2014

7/ YAW by Dani Couture (Mansfield) @MansfieldPress

— Carmine Starnino (@cstarnino) December 20, 2014

8/ Failure to Thrive by Suzannah Showler (ECW) @ZanShow @ecwpress

— Carmine Starnino (@cstarnino) December 20, 2014

9/ Some Dance by Ricardo Sternberg ((McGill-Queen's University Press) @scholarmqup

— Carmine Starnino (@cstarnino) December 20, 2014

10/ The Poetic Edda by Jeramy Dodds (Coach House) @jeramy_dodds @coachhousebooks

— Carmine Starnino (@cstarnino) December 20, 2014

The Artful Voyeur

Bert Almon praises the concept behind Michael Lista's new collection:

Dante, one of the poets Lista alludes to frequently in The Scarborough, tried to represent the Devil at the end of Inferno; the description is powerful but falls short somehow, just as attempts to take us into Hitler’s mind are always problematic. Instead of depicting Bernardo, Lista focuses on a single weekend in 1992, Easter weekend—the days marking death and resurrection—when fifteen-year-old Kristen French was abducted. The point of view stays close to Lista himself, who, age nine at the time, experienced the anxiety that pervaded Scarborough, an atmosphere of terror he evokes very well. Events in suburban life resonate strangely with the tragedy performed offstage, and allusions to pop culture (like the R.E.M. song, “Superman,” played by Bernardo during the rape and murder) and folk culture (fairy tales are full of grisly murders) are functional rather than decorative. Lista gives his poems two pillars to hold up the diverse structure: the story of Dante and Beatrice and the story of Orpheus and Eurydice. Yet in The Scarborough, we know that Eurydice is not brought back from the dead, and Beatrice is not enthroned in heaven but rather buried in the woods. Lista’s ability to make every detail significant shows mastery. The allusions to voyeurism are especially chilling when the murderer is also a stalker—and the poet knows that the artist is a kind of voyeur as well.Lista's struggle with his own voyeurism seems to excite Jonathan Ball most about The Scarborough, a book he calls "a significant achievement":

When Lista turns his gaze away from French, only to turn towards this turning away, the poems draw their blood. They are part of a sadistic project. The project’s sadism lays bare the reader’s sadistic interest, and the media’s exploitation. Lista plays a dangerous game by picking this subject, but he knows the game, and knows its danger. When the poems stop being about what they are supposed to be about, and instead become about Lista’s hatred of himself for being powerless to help French, and for wanting to write poems about her, the book bleeds.

Friday, 19 December 2014

Amateur Hour

Arguing that Edward Thomas' poetry displays the "authentically crippled quality of amateur poetry," Craig Raine pushes against what he calls the "shared communal delusion" of Thomas' genius:

As a poetic theory, Frost’s ‘sound of sense’, the idea of breaking irregular speech cadence over a regular line of verse, is original, as Frost was well aware. Only the sentimental chauvinist would try to give Thomas priority. We aren’t dealing with Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. But Thomas’s champions routinely overstate their case. Remember that Frost had already written ‘The Death of the Hired Man’ in North of Boston, his second book. It was published very shortly after the two poets met for the first time. Frost had worked out his methods and principles and put them into practice. Thomas’s experiments are hesitant. He works, as Frost advised, from prose passages and produces what Larkin accurately called Thomas’s ‘fitful, wandering line’. We are also instructed to value the prose source less than the poetry it became. This is not as obviously axiomatic as we are frequently assured. For example, which is better, the prose of ‘the long, tearing crow of the cocks’? Or the versified elevation of ‘two cocks together crow, / Cleaving the darkness with a silver blow’ [of an axe]?He continues:

Is it the sad, ironic lineaments of Thomas’s biography—the rapid realisation, poetic fulfilment, just before the untoward death—that incline readers to magnify his achievement? Like Violetta in La Traviata singing that life returns to her—at the very moment she dies. Is it the opera in the life that persuades us to go easy on the succession of ineptitudes that makes up the poetic oeuvre?

Wednesday, 17 December 2014

Tell it Slant

Richard Harrison - The truth and the story from Sarah Howden on Vimeo.

Richard Harrison explains how metaphors combine truth and falsehood.

Richard Harrison explains how metaphors combine truth and falsehood.

Tuesday, 16 December 2014

Weights and Balances

Kerry-Lee Powell discusses how the extraordinary story behind her poetry debut, Inheritance, shaped her formal decisions:

The collection centres around a shipwreck endured by my father in the second world war, his subsequent struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder and suicide. I wanted the collection to function as both an elegy and a love letter to the world that made and destroyed him. The subject matter imposed a number of constraints and meant that I was working with a subdued palette. Much of the rhetorical flamboyance that I admire in my fellow Canadian poets would have felt out of place. As the book approached publication, I became anxious about the emotional intensity of many of the poems. But it struck me that the forms needed the emotional intensity, would have been just so much dead wood without that heft.

I am a sound-oriented writer, and tend towards rhyme and slant rhyme and hard Anglo-Saxon stresses even in my fiction. I felt that working with older forms suited the outward theme of the collection. But there were other qualities, the doomed logic of the sonnet, the obsessive-compulsive repetitions of the villanelle that seemed ideally suited to the subject of mental trauma.

I don’t necessarily see myself as a formalist. Part of the pleasure of poetry for me, whether it’s free verse or conceptual or formal, is to find the patterns and constraints in any given piece. Are they conceptual, tonal, emotional? Where are the weights and balances? I find it hard to appreciate poetry that is shapeless or has too many false notes.

Labels:

Inheritance,

Kerry-Lee Powell,

Lemon Hound

Monday, 15 December 2014

Sunday, 14 December 2014

Sunday Poem

GIVEN

The secrets of losing recede until regret

is the only expression: instruct in error,

in the luck that flung you into wonder.

I've held you evenings in a briarpatch,

spitting lullabyes that permit a temporary claim.

Song of diamond, ease, mortal wound, the shared cry

that you were never mine as I am not yours.

Fathers distinguish love's night terrors from dreams,

years on. Your own sons will long

for bedtime stories, and you too will spill

the secret I'm trying to tell: our feelings are am,

what will be. By day we play, are hurt within

protectorates of choice. I can't choose.

You were given to me. To lose.

From We Need Our Names (Anstruther Press, 2014) by Shane Neilson

Saturday, 13 December 2014

The Poet Who Vanished

Ruth Graham sets up the central mystery around Rosemary Tonk's reputation:

There’s something unnatural about wildly successful people who decide that, actually, they prefer to be anonymous after all. What kind of person chooses to forfeit the rewards of fame: the praise, the power, the prestige? We might say we admire them for eschewing the worldly, but there’s an edge of resentment to our fascination too. It goes against human nature.Neil Astley goes into some detail about what caused Tonks, as one poet put it, to "evaporate[] into air like the Cheshire cat":

In poetry, the most famous example of such a retreat is Arthur Rimbaud, who quit writing at 21 after five years of blazing innovation and productivity. Rimbaud spent the rest of his short life traveling, and he became one of the first Europeans to visit Ethiopia. His letters show him apparently consumed with his work as a trader. Critics call his abrupt abandonment of his gift “le silence de Rimbaud."

Decades later, a London poet named Rosemary Tonks would name Rimbaud as one of her main influences. If she was not quite the scandalous sensation of her forebear, she was nonetheless respected, and she ran with a bohemian crowd. Tonks published two collections of poetry in the 1960s, along with six novels and frequent reviews. Philip Larkin corresponded with her and anthologized her. Critics took her seriously; Cyril Connolly praised the “unexpected power” of her “hard-faceted yet musical poems.” And then, quite suddenly, she disappeared.

The literary world both attracted and repelled her, and she was to turn against its materialism, false values, betrayals and indulgence, as she was to follow Rimbaud in renouncing literature itself: "The mistakes, the wrong people, the half-baked ideas, / And their beastly comments on everything. Foul. / But irresistibly amusing, that is the whole trouble" ("The Little Cardboard Suitcase").Tonks became a semi-recluse, devoting her remaining days—until she passed away in April of this year—almost entirely to the Bible. Bloodaxe recently reissued her two poetry collections, unavailable for forty years, under the title Bedouin of the London Evening: Collected Poems. But Hillary Davis reminds us that rediscovering her work also means confronting the literary cost of Tonk's decision.

Her mother's death in 1968 was the first in a series of misfortunes and crises that sent her life spinning out of control: a divorce she didn't want; a burglary in which she lost all her clothes; a lawsuit costing thousands of pounds; and ill-health, including incapacitating neuritis in her left arm and one good hand (her right was withered from polio). She turned her back on Christianity, believing the church had failed her mother, and instead looked for help from mediums, healers, spiritualists and Sufi "seekers". The inspiring presence in her house of a collection of ancient artefacts, including oriental god figures, led to her approaching a Chinese spiritual teacher and an American yoga guru. All these she repudiated in turn.

After her marriage collapsed, she found herself living alone, just a few doors away from her ex-husband (soon to be joined by a new wife), doing Taoist meditation, writing reviews and working on a new novel. She later attributed her next life disaster to difficult Taoist eye exercises, which involved staring for hours at a blank wall, turning the eyes in and looking intensely at bright objects. In 1977, on New Year's Eve, she was admitted to Middlesex hospital for emergency operations on detached retinas in both eyes. This was her reward for "10 long years searching for God". Returning home after a month's recuperation at a health hydro in Tring, she found herself totally helpless. Hardly able to see beyond a few feet, she rarely left the house, couldn't cook and became emaciated, all the time suffering from agonising pain in her eyes and permanent headaches.

The poet who most comes to mind when encountering Tonks is David Gascoyne. The comparison appears at first sight instructive: their best work written by their late thirties, a powerful sense of their own destinies as poets and of dissatisfaction with the flawed world which greeted them, descent into mental instability and then silence. But the contrast is equally illuminating; whereas Gascoyne’s voice matured from the Surrealist excesses of his youth into the most serious examination of man’s relationship to God and mortality—as in the sequence “Miserere” and the metaphysical poems—Tonks remains frozen at an early stage where the work has not yet settled. As with other poets, though not all, who stop writing young, she does not often get beyond an anger and an attitudinizing which are essentially adolescent. Quite a few of the poems are, moreover, very inchoate in a way which does not spring from genius or the “dérèglement de tous les sens” but merely a failure to master her material: “He, kneeling, with the moonlit sight of thieves, / Begged the ounce hog of the hedges she would seed / A touchy litter of her vermin commoners / That, gentle, he find syrup in his torn lack mouth / Before the radiant traffic of space / Cut to pieces the palm of his hand”. So, although there are indications of movement away from the claustrophobic interiors of Tonks’s self-consciousness, it is impossible to say what a more assured body of her work would have looked like, had her poetic career continued.

No Mystery

Danny Jacobs unpacks some of the qualities that make Anita Lahey's book of criticism, The Mystery Shopping Cart, so special:

Lahey rarely falls into the common traps of the reviewer: vague descriptors, scant quotation, goofy swagger, and forced conclusions that result when a stumped or bored critic tries to jam the square peg of a poet into the round hole of a preconceived poetics. The outcome is essentially jargon-free reviews that contain adept interpretations of representative lines. Lahey is confident enough not to equivocate; she gets to the heart of what a poet is trying to do, and with aplomb—all we can ask for from a reviewer. When she’s on, when her enthusiasm is palpable on the page, she has a way of getting at a poet with just a line, a meaningful summing up in a deftly worded phrase: “Davies has a convincing way of turning one thing into another simply by letting us in on the revelation-in-progress” or “Though it fumes, [Owen’s] poetry does more; it has become that finely wrought thing on the other side of anger: what we call art.”

Jacobs also singles out one of the book's most intriguing aspects:

Throughout the book, Lahey makes the peculiar and perhaps risky choice of adding afterwords to most of the pieces. These short additions, no more than a page (often less), may grate on some readers. However, the afterwords ground the book and serve to connect the pieces through a “present” voice. Among other things, they are background tidbits, asides, second-guessings and admissions. After her long essay on P. K. Page, she amusingly tells us that she “tried the glosa and failed. Tried it time and again, with godawful results.” She sometimes questions her reviews in the afterwords (“Was it fair to review Avasilichioaei’s first book alongside her translation of Stanescu?”): the present self reviewing the past self. The afterwords remind us that reviews (and our opinions) are hardly holy writ, a valuable lesson in a book of criticism.

Friday, 12 December 2014

Verbatim

"There is a good reason most reviews of poetry are so dull, and it's not just because the same can be said for most poetry. It's true that review editors tend to assign books of dull poets to critics of congruent dullness, but even zany poets are likely to inspire dull reviews. The reason is this: poets are regarded as handicapped writers whose work must be treated with tender condescension, such as one accords the athletic achievements of basketball players confined to wheelchairs."

From The Castle of Indolence: On Poetry, Poets and Poetasters by Thomas M. Disch

From The Castle of Indolence: On Poetry, Poets and Poetasters by Thomas M. Disch

Wednesday, 10 December 2014

The Domain of Risk

Michael Hind takes the measure of the the late Michael Donaghy's newly released Collected Poems:

It remains an abiding concern whether the Collected is the product of a post-mortem ruckus between academics and editors, for example Larkin, or the fidgety self-arranging of a still-living poet, as with Derek Mahon’s ongoing reshuffles of his work through a series of Collected editions (in this respect, he is the closest we have to an Irish Walt Whitman). All of this is informed by death, of course; very few poets are more valuable alive than dead, and very few want to be, if we take seriously the idea that a poet is seeking to find some words that will hitch a ride on the collective unconscious into the future (Plath’s “indefatigable hoof-taps” come to mind). Although he did organise some of his earlier work for republication, Michael Donaghy never got the chance to arrange his own Collected edition or to cull parts of his work for a Selected Poems (in some respects an even more radically demanding type of book for a poet to produce), simply because he died too young (in all senses). Ten years after his death, Picador has produced a paperback edition of his Collected Poems after a five-year wait, decorated with a sumptuous black-and-gold representation of what looks like either a seismograph or the graph on a lie detector; either way, it is a significant choice: the colours suggest a casket, the image an announcement that the time has arrived for canonical weighing and measuring. We are back in the domain of risk.

Speaking Rock

Mary Dalton tries to define what sets Newfoundland poets apart:

What I see as distinguishing Newfoundland poetry—and I am talking here about the island, as Labrador has its own traditions and story which have not yet been fully explored—from that of the other three Atlantic Provinces, perhaps, is a closer relationship with the speaking voice. Even now, with all the homogenizing influences of mass media, speech in Newfoundland is distinctive; there are various dialects to be found throughout the island. Scholars of Shakespearean English find continuities in the northeast of the island; the anapestic rhythms of Irish ripple in the speech of many areas of the Avalon Peninsula. The speech is richly idiomatic, concrete, close to the body. As well, traditions of storytelling and singing have been and still are very strong here. The distinctiveness of Newfoundland poetry lies, at least in part, in the ways in which the oral culture has influenced the writing.(Print by David Blackwood.)

Tuesday, 9 December 2014

Domestic Poetry Exploded

Aptly describing it as a "collision of danger and decorum," Lorraine York is dazzled by Nyla Matuk's debut:

In Matuk’s Sumptuary Laws, the domestic is deeply infused with the bizarre. A dizzying array of metaphorical pyrotechnics adorns Matuk’s description of the banal. “Sunday Afternoon Croquet,” for instance, a poem about playing that most placid of domestic lawn games, becomes saturated with repressed chaos; the poet imagines herself bending over the ball, “elfin green bitchy lady” feeling “like a mad Roman emperor with a history of failures / at miniature golf”—a fabulously bathetic collision of the bizarre and the tame. For Matuk, this is life as we know it: the everyday suddenly disclosing its grand theatre. Her collisions of language and metaphor are so daring, the jumps between image and image so precipitous, that she provides, at the end of the volume, a gloss on some of the references. This is more than a paratextual glossary, though; the entries themselves refuse to follow the convention of explanatory material acting as a taming explanation. The most witty of these is the note explaining that her description of “Petit-four disciplinarians” refers to six- or seven-year-old bossy little girls: “Sometimes these girls are dressed in the colours of buttercream icing on petit-fours, but they are sometimes just little fucks.” Matuk’s poetic lexicon may be ornate, but it refuses the cloyingly sweet; here is sweet “feminine” domestic poetry exploded.

Sunday, 7 December 2014

Sunday Poem

1959

Launched on abracadabra, searching steamed rock

ruled by the lizards. Where we arrived it stunk

from extinction and exhale. One of our crew

whispered, We have landed on Venus. The navigator

believed him and died from the burn in his lungs.

Our map predicted mountain ranges, chartreuse

lakes. Instead, hot quarries swallowed sunrise,

we kept time by quake strength and sulfur hallucination.

Our instruments lost pace with the paramecia. The rust

was proof of oxygen. Still, we grieved for future

suffocations. Our vessel started as a notebook sketch

from a dream seized by stiff drinks. Escape muscles

calcified, reentry theories perished and the bones emerged

as decorative fossils. The dead machines, benign constellations

tainted each drop of our blood water. Amnesia became

magic. We dared believe we deserved the home we had.

From Everyone is CO2 (Wolsak & Wynne) by David James Brock

Saturday, 6 December 2014

The Long Game

To love poetry, argues Michael Hofmann, means reading less of it:

I think poetry is always one or two poets away from extinction anyway. If it’s any comfort, it’s not a living tradition—it doesn’t depend on being passed from hand to hand. It could easily go underground for a couple of decades, or a couple of centuries, and then return. People disappear, or never really existed at all, and then come back—Propertius, Hölderlin, Dickinson, Büchner, Smart. Poetry is much more about remaking or realigning the past than it is about charting the contemporary scene. It’s a long game. Also, it’s not about extent, never about extent, not about numbers or range or choice. It’s not a supermarket. You can’t roam around, and read x on one day, and a the second, and b the third, not if you have taste and take it with you everywhere. It’s a condition of poetry that you can’t read everyone. What is it Lowell’s Harriet says— “You can’t love everyone—your heart won’t let you.” It’s about depth, and what you find in it. The question isn’t, Who would I like to read now for the first time? It’s, I have these six poets. I must have read them all a hundred times. They’re just about all I read—it’s years since I read anyone else. Which of them do I feel like reading for the hundred-and-first? Whose books do you wait for? That’s the question. Precious few.

Friday, 5 December 2014

Indie Jeunesse

Michael Lista's pick for best lyrics of 2014? "Blue Boy" by Mac DeMarco:

Every generation gets the asshole musician it deserves. The baby boomers had too many to count, but let’s settle on the elliptical oracle of Bob Dylan that Pennebaker caught on film in 1965, whose mannered transcendentalism and moral pretensions, like his generation’s high-mindedness, would be made ridiculous by the Chevy ads and Christmas albums that were to follow. We, their children, have Mac DeMarco, Edmonton’s crudest emission since an oil pipeline. Drunken hipster nonpareil, this is the dude who once made an AIDS joke at Freddy Mercury’s expense—so ironic, bro! Over at Pitchfork, a cohort of aging, over-refreshed babies lapped it up.Check out the CBC page for other selections by authors, including Sean Michaels and Saleema Nawaz.

So it came as a surprise when he titled his glorious 2014 record Salad Days after a line from Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, headstone for the youthfully headstrong: “My salad days/ When I was green in judgment, cold in blood/ To say as I said then!” As Cleopatra apprehended the end of her youth, DeMarco realizes that the millennials’ skinny jeans—six years out from the financial crisis, and after so many PBRs—no longer fit. Future rock aficionados may look back on this record as the final, magnificent cresting wave of hipster, indie jeunesse. As DeMarco sings, over yacht rock for the yachtless generation: “Sweetheart, grow up.”

Thursday, 4 December 2014

Jean Béliveau 1931-2014

By Crystal Béliveau

It's amazing to me that, a few short years after winning his first Stanley Cup, Jean was sitting on a sofa on a farm in Saskatchewan paying a visit to his prairie relatives, many of whom he didn’t even know. I’m sure all of my aunts and uncles have their own version of that photo. It is the stuff of family legend.

I spent my high school years wearing number 4 in Jean’s honour, and running from my bedroom every time Dad shouted, “Jean’s on TV!” (He only did that with two subjects: Jean Béliveau and nature shows. “Chrissy, come see the fox!” and “Chrissy, come see Jean!” were the rallying calls of my youth.)

When I moved to Montreal in the mid-nineties, I sent a letter to Jean via the Molson Centre announcing that I was a second cousin from Saskatchewan, that my father was George and that my mother Marianne was coming to visit. Would he be so kind as to meet us for coffee?

Weeks later, as I was running out the door to sling popcorn at the Cinéma du Parc, the phone rang. It was Jean saying of course he remembered my parents, and extending an invitation to come for dinner. I was stunned. I kept the event a secret from my Mom and didn’t tell her where we were going when we headed out (in part because I didn’t want her to realize that the metro ride to Longueuil would involve us hurtling under the Saint Lawrence River in a tube: she hated the metro enough as it was).

I brought a bottle of dep wine (I didn’t know better then) and we spent the evening in their back yard gazebo listening to Jean and Elise tell stories of how they met and his early days in hockey. After dessert, Jean made a phone call. As planned, my brother Dennis answered and handed the phone to Dad. Jean said, “Hello George, how are you? Do you know who this is? It’s Jean Béliveau.” (Dad didn’t believe him at first, which was also kind of wonderful in its own way.) Jean went on to tell him who his dinner guests were, and back in Wolseley the next day, Dad became the star of coffee row.

That was the first of many gracious offers Jean extended over the years. When my brother Duane came to visit, Jean and Elise came to my humble Saint-Henri apartment for dinner and gave us their seats for the next game. (My brother pretty much started vibrating at that moment: my scalper tickets up in the nosebleed section couldn’t hold a candle to those). When my sister Colleen came with her husband and kids, Jean took the time to meet us for lunch at the Molson Centre. My nephew Nathan posted a photo from that day: he is wearing a Leafs jersey (yes, my sister married a Leafs fan) and Jean, smiling, has his hands planted firmly on his shoulders. Over the years, he sent autographed pictures to both Colleen and Colette to help raise money for their sons’ minor hockey teams. When my uncle Roger died last year, my cousin Mark asked for Jean’s number and was deeply comforted by the conversation he had with him.

Jean was that kind of man. He had a talent that made him legendary, and a humility that made him ours. Until his health started failing, he personally responded to every letter and phone call he ever got. I know, because he responded to mine, and I have been humbled by that ever since. Rest in peace, Jean. You made us all so proud.

Monday, 1 December 2014

Restaged Debate

Five years after the event, Richard Harrison's report on my "cage match" with Christian Bök is finally online.

As is almost always true of such staged debates, much was said. And much was left unspoken. Then we all went to the lobby for refreshments. It might have ended there. But between what was discussed and what was left unsaid that night, in the nature of the audience drawn to two poets whom many regard as antagonists, and from all that led up to the event—including Starnino’s Writer-in-Residency at Mount Royal and the publication of the second edition of Bök’s Eunoia—emerged a wide-ranging, deep and fascinating discussion about the nature of poetry and of the mind that writes it. What follows are the conclusions I’ve come to so far as a participant in a symposium spread out across the offices, hallways, bars, classrooms and various virtual spaces in the community created by the Cage Match itself.It's a long essay, but well worth your time.

Labels:

Cage Match,

Christian Bok,

FreeFall,

Richard Harrison

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)